Some Men Have Mistaken me for Death

Linda Stupart

She is typing with one hand on the keyboard and as well as being frustrating – letters slip, words come into meaning too slowly, her right hand aches – it makes her feel further from both the machine and this language. She looks directly at the keyboard for the first time since she was a child, and words still come out wrong – is becomes us, for example.

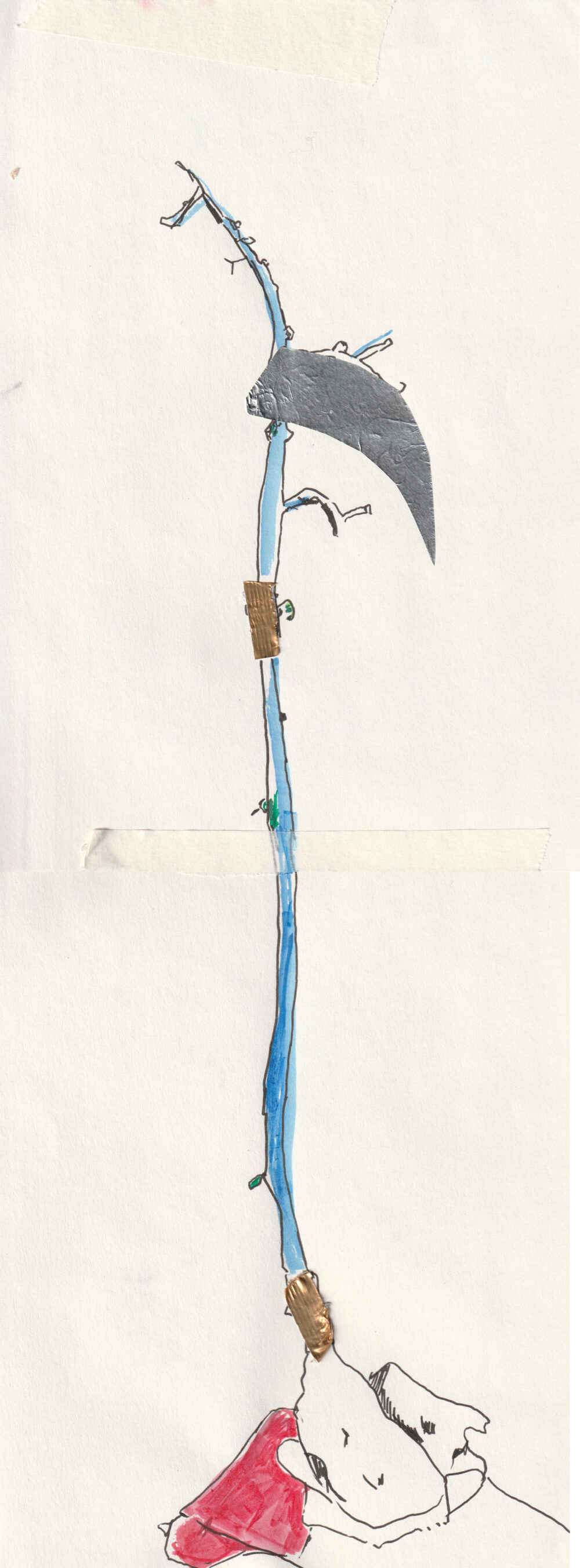

She is writing with one hand because the other hand is inside a ceramic cast, though it is not injured. Her arm sits comfortably inside the object, riding slick bumps. One finger protrudes, like a teenager pulling down an oversized army surplus jumper, thumb through the hole

Watching fireworks

Since she was a small child she had a recurring dream. In the dream everyone she loves is dead. The dream is pale pink and when she wakes up her mother tells her that dreaming of death means pregnancy, or multiplicity, or more.

Trauma is also the language of death.

PTSD is always in the present that’s why you can’t hide from it. As if there is a hole between timelines, or, a glitch. Your body in the present disappears, or, is overlaid by your body of the past, the no-longer-your-body of the event. We are told that the most dangerous part of time travel is the possibility of meeting a version of yourself somewhere along the way.

Once she saw death on the corner of a street on a hot day. She was on the way to her friend’s house to smoke weed to help with her period pains. Doubled over in pain, multiplied by blood loss, she is also standing across the street and she sees herself and also death standing on the corner of the street.

A man who I had had sex with after our friend had suicided told me I was the physical manifestation of his mourning. That same year a man who I had had sex with in somebody else’s bed and who was extremely beautiful but had a girlfriend who was probably also beautiful said to me ‘I’m just really good at incorporating the lost object into my melancholia.’ Both of these men who I have slept with believe my body to be death or to be lost. Perhaps, since – perhaps since it feels that these men were not entirely concentrating when they slept with me or dumped me, I could build a new body to be their substitute object instead – the pillow under the duvet in your mother’s house, with hair collected from the tails of horses substituting yours, across the sheets. Then she could stop being death perhaps, after Capitalism no one will have to work.

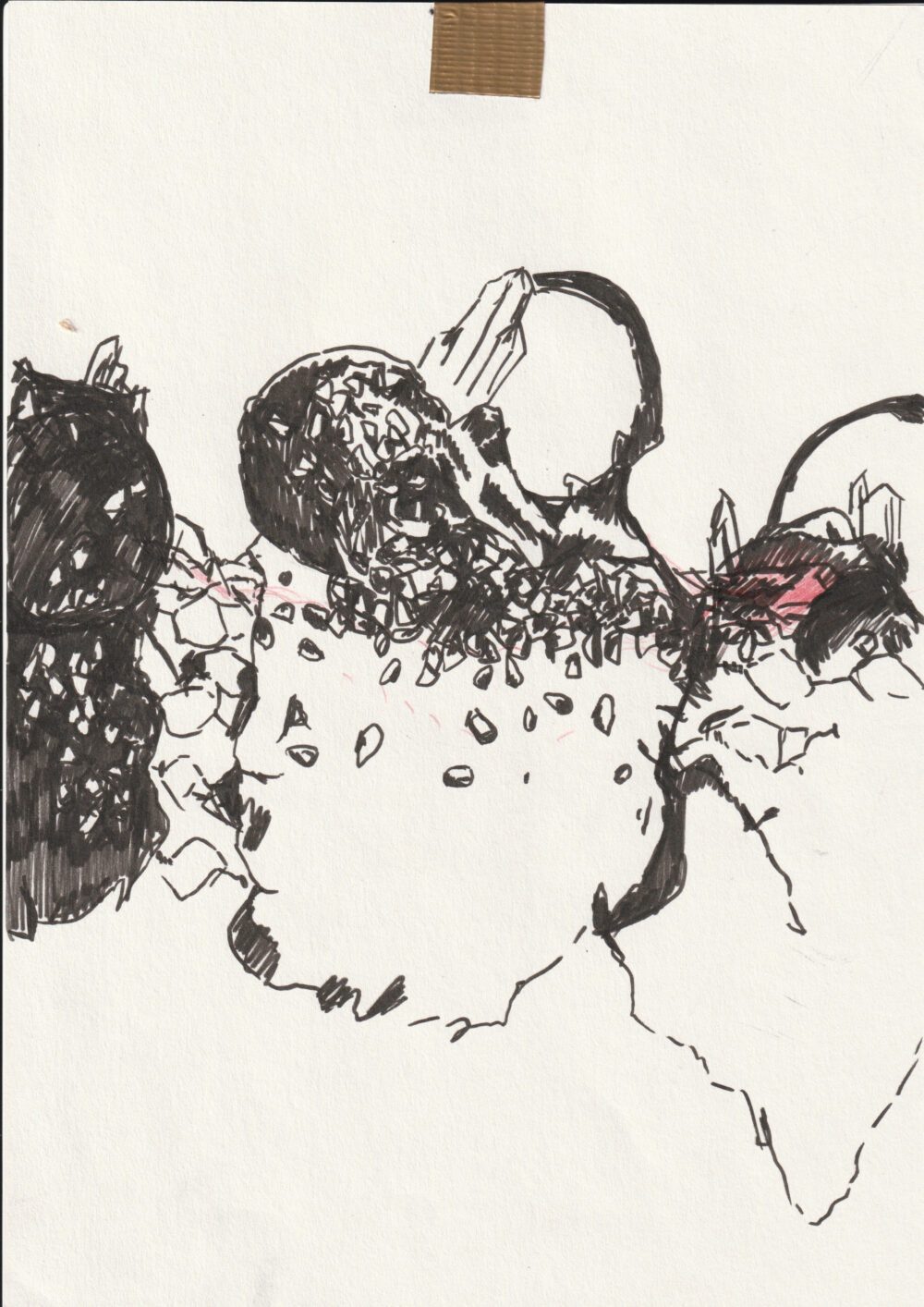

Builds a body out of crevices and absences and mud and shit and hair. Paints it pink and when she goes to lay it in her bed, stubs her toe on an improper thing at the bed’s edge. Lifting up the covers she finds an object almost exactly like the one she has just made, its calcified sister and her sister and her sister’s sister, forty hardened bodies cast from folds and holes and gaps between her body or the bodies of dead women or their children in her dreams.

I want to write this fast, like running away from the objects under the bed, or like dreaming or dancing, or biting into clay – pulling out a splinter – but instead my one hand continues through repetitive constitutive failures, while the other strokes the inside of your object, which is also cold.

Slow writing is like leaving the warmth of a computer to somewhere else but it is also like losing your self or your ideas before you can say them or it is like breaking a connection with cyberspace or the world, which is like death. But without a hand or limb inside the object, she cannot access: the things under the bed, her dreams, the horse’s twitching ear, the earth, her other bodies, the future.

So she places the ceramic cast over her left foot. Her big toe fits through the hole where her thumb fit through the army surplus jersey and where she broke her foot rollerblading (I do not trust bodies that have never ceased to be whole in this or similar ways). Foot inside clay and fingers on keyboard she is between at least two worlds – death, she thinks, is also everywhere at once.

That night she slips into her bed beside her pillowdouble, who sleeps nearer the door so that if the men or any body comes expecting death, they will find her pillowdoublebody first, which will bide her some time to escape at least.

When they do come through the door, she rolls away and under the bed sliding mercury between the splitting calcifications of her dreams. A smile twitches under surfaces and she sinks as liquids do beneath the floorboards and down into the ground and below the surface to the very center of the earth where a group of women sit and lie and dance and squelch cold clay around a fire. Throwing their impressions into it till they

This pile is growing so big it has reached the surface

Points are starting to appear above ground

There is no time in the center of the earth except the increasing pile of un-objects cast of the holes made by women’s arms and toes and thighs. And now the pile is starting to break through the surface and into the world and present tense. She says ‘some men have mistaken me for death, but I do not believe I am death, and I do not like the hours or the uniform or the job or any job can you help me women under the earth’.

And the women smile and one who looks exactly like her says to leave her pillowbody horse’s hair in her bed upstairs, that those men are already fucking it, and join them outside of time, a place you can only find inside a body that moves so quickly between it, and help us to build the world.

Linda Stupart is an artist, writer, and educator from Cape Town, South Africa. They completed their PhD at Goldsmiths in 2016, with a project engaged in new considerations of objectification and abjection. Their current work consists predominately of writing, performance, film, and sculpture, and engages with queer theory, science fiction, environmental crises, magic, language, desire, and revenge. They are also a lecturer at Birmingham City University, in the School of Art.