Chain Smoking Poetry

Diana Hamilton

In psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott’s Playing and Reality, a patient suffers from persistent states of immobility and inaction—what Winnicott calls both dissociation and “thumb-sucking”—and wastes away her life lying perfectly still, depressed because she cannot read or paint. Winnicott set out to help her understand the difference between fantasying, reality, and dreaming, especially to understand that there was more hope for creativity in dreams than in the waking fantasies that left her in bed, even if they allowed her to retain a sense of control:

As soon as this patient began to put something into practice, such as to paint or to read, she found the limitations that made her dissatisfied because she had to let go of the omnipotence that she retained in the fantasying. (40)

I think this is why poems and art turn so often to dreams—not because they have any particular claim to the unconscious, not out of some misplaced nostalgia for surrealism, but out of the sense that dreaming involves creative activity that is hard to mistake for repression (unlike other behaviors—going to work, exercising, tidying up—that, though they may be active, are tied up with a repressive sense of obligation). In terms of “doing something,” dreaming is on the same order as reading a book, an active passivity that invites interpretation. Winnicott would take it further, as he argues that “dreaming and living” are “two phenomena that are in many respects the same” (42).

When I first read the title poem of Kay Gabriel’s new book, Kissing Other People or the House of Fame, I felt jealous of the great busy-ness of her oneiric double—she has a better social life in her dreams than most people have awake—while I party hopped through her REM cycle. While I have, in my own work, tried to argue that dreaming is one form of creative writing, Gabriel’s speaker is more confident: the poet is a specialized dreamer, a pre-Freudian receiver of visions, and her dreams do their own interpretive work without need for the mediation of the dreamer’s waking reflection:

I dream of the latin verb errare meaning to be mistaken the translation in the dream is “you’re pretty” and a fashion designer names a dress “This is the Poem of the Mammalian Surface” (39)

It is wrong to bring Gabriel up here, as her book holds psychoanalysis at arm’s reach and could not be fairly accused of proposing some psychological understanding of living well. I mention it anyway because I am interested in a posture that she borrows from a few forebearers. The second half of her title come from Chaucer’s House of Fame, started on some 14th-century December 10th, where he announces the singularity of his accomplishment:

Ne no man elles, me biforn,

Mette, I trowe stedfastly,

So wonderful a dreem as I

The tenthe dide of Decembre,

The which, as I can now remembre,

I wol yow tellen every del.

In Midwinter Day, written on 12/22/1978, Bernadette Mayer reprises this stance:

For never, since I was born,

And for no man or woman I’ve ever met,

I’ll swear to that,

Have there been such dreams as I had today,

The 22nd day of December,

Which, as I can now remember,

I’ll tell you all about, if I can

Gabriel doesn’t imitate this rhetorical move on the level of the line, meaning there’s no “never before has a woman had such dreams as I had between April 2019 and April 2020,” her longer temporal constraint; the closest we get is “I will never again / have a headache this Feb.” She borrows more of Mayer’s investment in collective living and social documentation, and in the ability of a single poetic decision to produce a book, than she does this suggestion that the poet is the unusual recipient of great ideas in sleep. Still, she shares their sense that a dream is worth relaying in detail. My interest is in what Chaucer and Mayer make possible, in Gabriel’s work: how one of the many conditions that constrain our writing are the books of others that we happen to have read.

While critics continue to beg novelists to write about the lives of someone other than writers, poets do not care. Unless you choose the strange (and often offensive) path of the persona poem, your “speaker”—however much we are trained to recognize this as an invented subjectivity, separate from the author’s—is still, by necessity, someone in the position to be the first person of poetic language. This gives the poet permission to write about the most interesting part of their life: the other books they are reading.

To live only from book to book, from dream to dream, without much interruption, is to be fairly active. Winnicott offers a case study to support his book’s main purpose: it is “a plea to every therapist to allow for the patient's capacity to play, that is, to be creative in the analytic work,” an allowance that requires the therapist to be mostly silent, not to demonstrate too much knowledge, and not to interfere. This leads him to describe a woman who relies heavily on memorized lines:

We now talked about poetry, how she makes a great deal of use of poetry that she knows by heart, and how she has lived from poem to poem (like cigarette to cigarette in chain-smoking), but without the poem’s meaning being understood or felt as she now understands and feels this poem. (83-4).

The patient has just quoted a line of Gerard Manley Hopkins—“Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.”—as an explanation for her searching for some evidence of her self’s existence; the conversation about this line, spread out over two hours, leads her realize that she’s brought a self into being.

In “The Poem They Didn’t Write,” Jameson Fitzpatrick may not bring a self into being through the lines of others, but she does invoke a hypothetical poem that could:

The Poem They Didn’t Write was about the brilliance of women,

their friends, how many of their most enduring relationships began

with the two of them recognizing the animal of the other in their poems.

Was about identification.

Reproduced Anna Swir’s “The Same Inside” in full.

Whenever someone asked about their favorite poems they said

that one. Also: Anne Sexton’s “Just Once.” Also many poems by women

about men, but (just once) let’s leave them out of this

[ . . . ]

In the Poem They Didn’t Write, they felt free to say, “I’m not one.”

The Poem They Didn’t Write was an effort to correct

the image they saw reflected at the vanity.

In this real poem about the hypothetical poem Fitzpatrick “didn’t write,” the image in the mirror can be corrected by a book list, by “an account of their literary education,” by the songs that have sound tracked life, and by memories of all friends with whom one has confused tears and laughter. And though this poem is “not interested in psychology,” Fitzpatrick’s speaker gets to have it both ways: like Winnicott’s patient, they can retain their omnipotence by leaving the poem idealized, unwritten, only described, but they move past mere fantasy by recording its proposal.

Earlier in Gabriel’s book, she writes, with Cam Scott, “A Less Exciting Personism for the Less Fabulously Employed,” about another merging of subjects:

About bathos they were spot-on, those studious pervs:

In the path of totality the sun is blotched by a

thumbprint

Things trade places on approach –

look how easily it transforms into its opposite, a doctor

Is that my body odor or my roommate's kush?

The poem’s form interweaves two monologues, switching every other line (perhaps rejecting O’Hara’s admonishment of “propagandists for technique”), such that I feel compelled to read it four times: the first straight through, the second skipping the every other line lines, the third reading the lines I skipped in the second, the fourth straight again. Here, I remember that the occasion for O’Hara’s original manifesto on personism was someone else’s complaint that he wrote a poem “that can't be got at one reading.”

In Ted Dodson’s “The Language the Sky Speaks,” a long poem in his recent book An Orange, the speaker finds himself “midway into a routine of episodic anhedonia / where desire escapes me entirely” (83) (echoing both Winnicott’s daydreamer and Dante’s opening to the Inferno, replacing “our life's journey” with a depressive state). He is resurrected from this hell by way of the consultation of a private document:

I keep favorite poems in my email drafts:

JA’s “When the Sun Went Down,” those first lines

I’ve internalized, Baraka’s poem to Jonas, a late poem

from Barbara Guest where “…skies / Throng into themselves…”

Corina’s “Pro-Magenta” because I hear her voice when I read

“…be a love / That does not know / How to know /

Human genre crashed on / The purblind sea…”

Kevin’s “The Gifts of San Francisco” that I now always have on hand

since I looked for it [ . . .]

This list goes on for another 50 lines—friends appearing by first name, the famous given more formality—often including details of where he first read them, or where the poet first wrote them, and it ends with “Reverdy’s ‘That Memory,’ the most beautiful poem / to me in any language, which I save not only for myself.” Reverdy’s “Ce Souvenir” also provides the poem’s epigraph and opening line. But while Dodson singles him out, the poem that lives through other poems is always setting something of the experience of reading aside for another, or inviting the reader to catch up, in some way, with the speaker’s emotional experience.

Dodson is saying: here is the list of poems that I keep on hand to live through, when unmediated living feels impossible. As with Mayer, as with Gabriel, as with Fitzpatrick, this isn’t just an invitation to read, but to borrow the form, to make one’s own list. He ends this section by asking a question I could just as well ask myself: “why make mention of them together?” Like Dodson, I am not making an argument, but I am repeating some lines of gay poems that I love. I am seeing a form that I liked, and I’m repeating it.

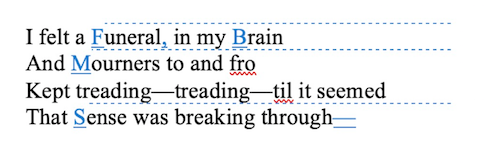

Last year, I started a failed project I was calling “Proposed Thought Replacement System.” The idea was to write a half-serious, half-ironically-despairing guide for how to replace intrusive thoughts with memorized lines of poetry. For the reader who happens to find themself suffering from the crushing repetition of “kill yourself” running through their mind or lips whenever they make a minor mistake, for example, I recommended reciting Emily Dickinson’s “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain” as a secular prayer. The point of memorizing is to have the poem available to you wherever you are, to try to get it stuck like the lyrics from whatever alt rock comforted you in puberty. Once you’re close, you write it down from memory, consulting the original to mark mistakes—

—until you find yourself released from verse, finally empty-headed.

The opening line is an objectively hilarious way to announce this particular ideation, for one, but its recitation also converts a private symptom into a social activity, asking your depression to dialog with Dickinson’s pacing Mourners. Ride a bike, recite it ten times, and speed up your pedaling for the fourth, best stanza, the noisy one, where “being” is “but an ear.” If, after that effort, “kill yourself” does not go away, but instead morphs into variants like “just put a mallet / to your head / and this will all be done,” I explained, it means Dickinson’s rhythm has started to win over your conscious mind; you’re close. But it hasn’t yet displaced the thought, so there’s still work. I suggested other poems for other problems: for the socially anxious who inexplicably find themselves drawn to sociality, for example, there would be Bernadette Mayer’s line “Perhaps is why you love the presence of other people so much,” from “The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica,” a poem about a panic attack.

This project failed, I think, because it was too focused (even if disingenuously) on the question of what could be curative for really existing, non-fictional people—for patients, really. Poetry is not self-help, at least not for the selves of readers or writers. I think the more interesting question is what internalized poems might offer to the speakers of other, future poems.

Diana Hamilton is the author of The Awful Truth and God Was Right.