Dance for Myself in Front of You: Mariana Valencia’s Album

Roy Pérez

“I’m not sure who will write a history about me”—Mariana Valencia tells us about a third of the way into Album—“so I’m starting now to help them have good notes. If I tell you about my thoughts, the notes in my dance books, my friends, my trips… then someone might be able to write my history better.”1 Rather than anxious or unreliable, the narrator in Album seems instead to take pleasure in sharing more in ideas than in biographical facts. The narrator/speaker/singer/dancer’s history in Album is a non-linear, multi-form collage that has no clear start or end and never feels exhausted of possible content. It’s as though queer storytellers are so accustomed to being misread and relying on gossip that we think of the archive as more of a live studio than a dusty vault, and narrative as an exercise rather than a document. We want histories that are better, if not altogether correct, complete, or true.

Album is a solo show roughly one hour long of choreographed poetry, live music, and improvised and scripted autobiographical storytelling in the form of loosely tied anecdotes, thoughts, and songs addressed to the audience—“a medley of observations” told in multimedia.2Brooklyn publisher Wendy’s Subway released the script of Album in a small volume that includes drawings and photos, with much of the monologue text visually rendered like concrete (or word-image) poems. As the title Album signals, the project works visually like gestural and textual collages and sonically like a mixed tape of thoughts and music. Both the live and published pieces are richly citational across form, including critical and admiring references to movies, dance, poetry, music, friends, family, and feminist and queer idols like Joan Baez, Roberta Flack, and Assotto Saint. In this way the speaker is spliced with other lives and the mediums with other media, assembled with a joyful and contemplative excess of self-disclosure that evades obvious artistic form or predictable emplotment.3

The intimacy that Valencia’s splicing together of herself and others enacts in Album is vital right now, two years into an almost global experience of lonely boredom, profound estrangement, and cataclysmic loss, in rapid rotation. We’ve had to find new ways to convene, overlap, intertwine, and be apart. The plots of our lives have been disordered, scattershot, by postponements, cancellations, disabilities, and disappearances. And the distribution of suffering has been uneven—as Valencia chants early in the performance, “someone gotta die so someone else can live.”4

Comparisons between HIV/AIDS and COVID have been useful at best, often facile, sinister at worst, but it strikes me that the current pandemic has a “calendar of loss” with which queers are familiar, through the proximity of HIV/AIDS, houselessness, and economic precarity in our collective plotlines.5 Queer and trans folks are intimate with disorder. We invent and schedule our own milestones. Our family might have no nucleus. Hormone therapy throws us back into puberty. Sexual emergence happens too late or too early or multiple times or not at all. We’re not strangers to loss and premature death. So while there’s nothing especially queer about nonlinear form, it may be that we have a special facility with improvised, creative emplotment.

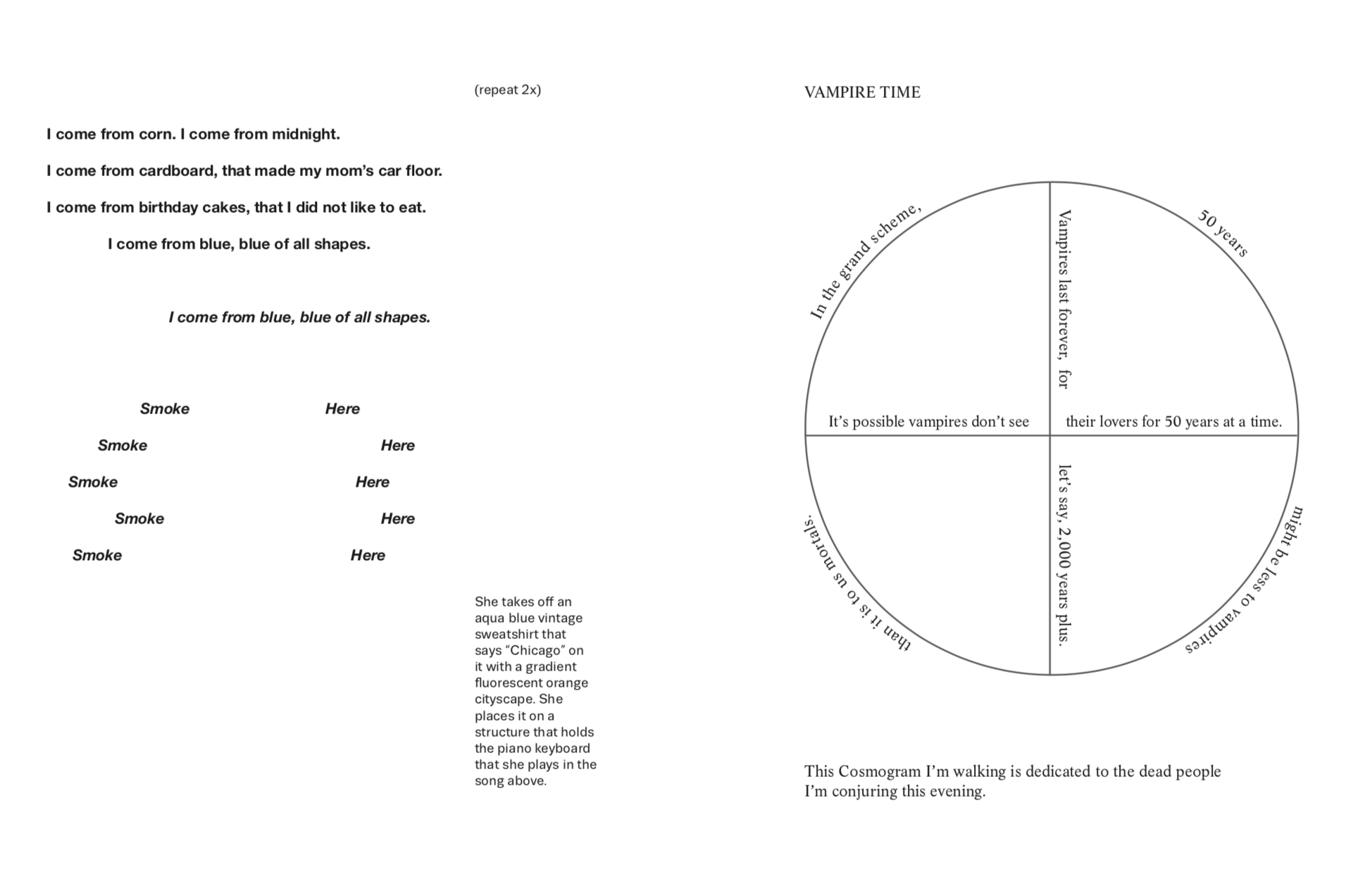

In Album Valencia calls this queer temporality vampire time.

Time is either short or long in mortal reality because of

its proximity to death.

For vampires, time = life forever so I’d rather think of

time in “vampire.”6

Immortality—vampire time—is a queer and vital strategy of emplotment to think our way out of the scarcity of time. Lifetimes are a glimmer but the past and future are with us, available for conjuring. Here in Album Valencia tells us that she is walking a circular cosmogram (pictured) to churn history, connect disparate nodes, and conjure the dead—in this instance, the late queer Black poet and activist Assotto Saint.7 “I like to think that I know you Assotto, in vampire years.” She recounts meeting Saint, a conjurer himself, for the first time, “a ghost in my room,” a set of eyes and then a mouth on a TV screen.8

You are proud of your role in the sexual revolution,

You speak beyond the screen,

You speak to me, finally to me.

You Assotto, don’t need me to tell you that you’re a star.9

Linear time would have us leave each other behind, but in vampire time, in star time, in queer time, we’re in constellation. Such dispersed emplotment of people, beats, medium, movements, and words is not formless, but it’s not static. Queer emplotment finds its forms as it goes.

Queer Line

EMILY BROWNLOW

Visited me in the studio when I started making this dance.

♪ ♪

She gave me advice to make this dance, she said,

“Give yourself a limit and only dance on this side of the

tape.”10

Emplotment, rather than plot, emphasizes the plasticity of time and order in narrative, the activity of disordering or reordering enacted by the artist. We might think of nonlinear emplotment as experimental or esoteric, as sophisticated or pretentiously obfuscating, as though there is true a chronology that undergoes heady sculpting. But (queers know) linear time is a conceit. There’s nothing more real than the arbitrariness of what happens in a life. Plot seeks order and it can be a violence or a consolation, but it’s no more linear than an artist’s re/arrangement. For queers, the way things go down is already a rearrangement of how they should have gone down, how we wanted them to go down, how we dream they’ll go down next time. There's nothing more queer than disorder.

Valencia draws the line suggested by Emily Brownlow with white tape stretched diagonally across the black floor of the stage. The performance I attended in 2017 at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art11, took place in a black box theater with spotlights fading in and out on various sections as Valencia moved (danced, shuffled, crawled, rolled) among a bench, a keyboard, and a handful of props. Throughout the performance, Valencia defies Brownlow’s instruction and dances on both sides of the line, such that the line is more of a companion than a “limit.” Or rather, it provides the formal limit Brownlow suggests by inviting traversal, back and forth and along.

The line is a poetic conceit—we agree it’s a limit, a boundary, and we also agree that it’s only there to be traversed. The line as queer form works here “less as a stagnant image and more as a vibrant visual sign that energetically communicates a sense of historical drama,” as Ricardo Montez writes about the lines Keith Haring brushed, in particular, across men of color in the 1980s.12 The line is not the story, the story is not beholden to the line, and the story is told all around the line. At times it provides an anchor, while at others it’s an opposite pole, and at others it’s in darkness and seemingly forgotten. Linearity is something we improvise, keep handy, to keep us steady.

All of this makes for an opaque style of autobiography if we measure an autobiography by its intelligibility. This opacity belies the sense-effect of intelligibility—the sense of narrative or aesthetic realism that we ascribe to linearity, or the linearity that realist representation is expected to honor.13 The moves among visual, physical, sonic, and textual forms in Album’s many manifestations (written and performed) turn our heads toward what autobiography does or can do, rather than what it tells us or documents. The self is an album, in that we are channelers and collectors of what forms us.

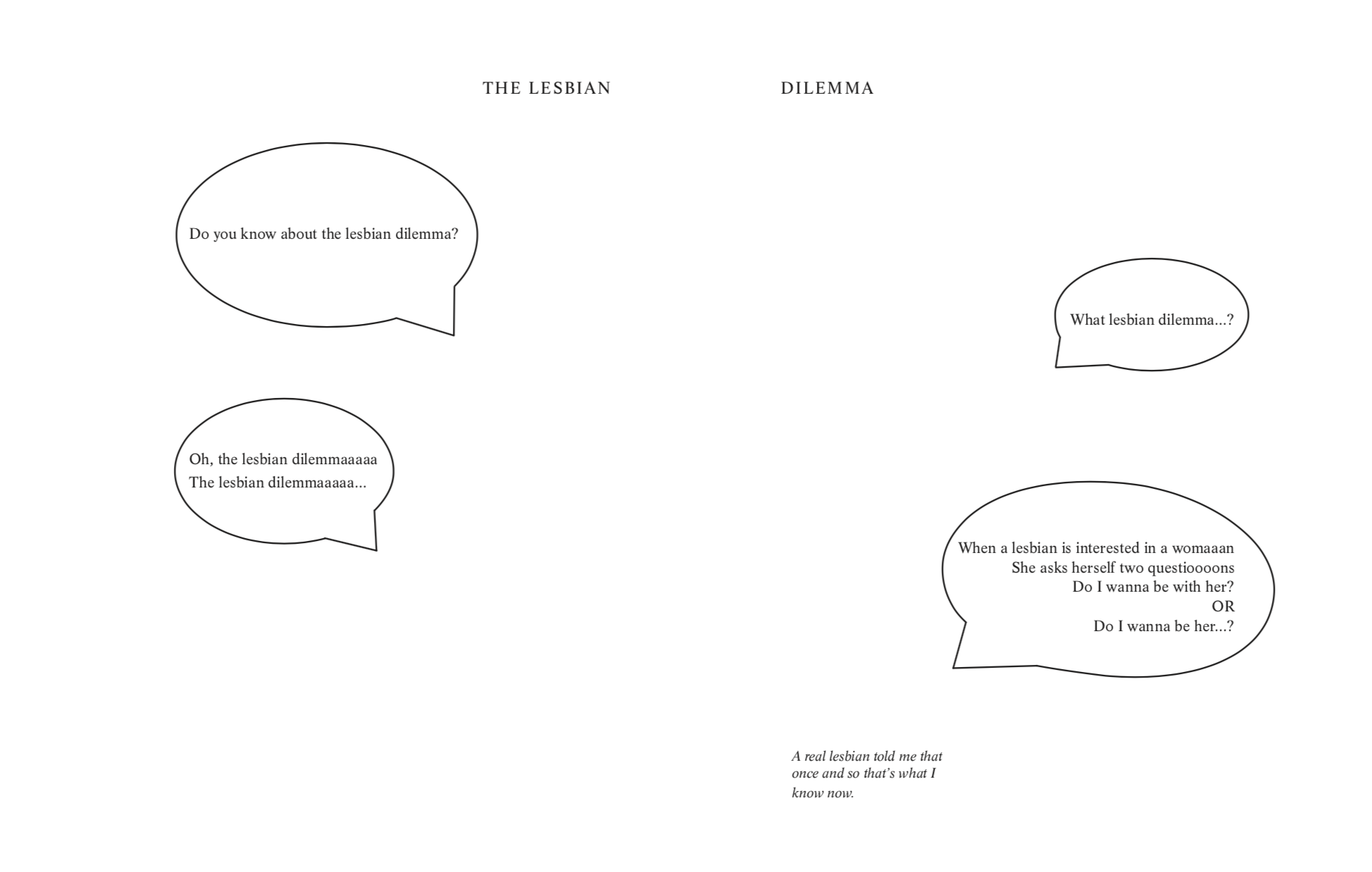

Do You Know About the Lesbian Dilemma?

The lesbian dilemma, as conveyed in song by Mariana Valencia while lying prone on the stage floor, one hand to forehead, dramatically:

When a lesbian is interested in a womaaan

She asks herself two questiooooons

Do I wanna be with her?

OR

Do I wanna be her…?14

Valencia performs this dialogue while darting between two spots on the stage, playing both roles in the conversation, enacting two women adjusting their hair as they chat. The lesbian dilemma is gay wisdom, a queer secret Valencia shares with the heterosexuals in the audience. Part of the secret here, the unspoken part, is that heterosexuality is a lie. Imagine experiencing desire as anything but this confusion between wanting and being. The conceit of opposite sexes implies that heterosexuals do not experience attraction as a desire to be the other, internalize what the other gives you, as though gender means you can’t overlap but only complement, or that you are fundamentally discrete beings. Falling for someone, Eve Sedgwick writes, is “a matter of suddenly, globally, ‘knowing’ that another person represents your only access to some vitally

transmissible truth

or radiantly heightened

mode of perception.”15

The lesbian dilemma, maybe, is knowing that this limit between me and her is subject to trespass according to the vagrancies of desire’s different forms of lust and love. Like linearity, queers know sex (as in sexual dimorphism) is a conceit: we agree there are differences, but we know the differences are not all that consistent or real. Desire may seek a sense sameness or difference at different times to get off or to feel a certain thing, but is not reduceable to it. The tension between the two gives form to who we want to be.

Dance for Myself in Front of You

Album doesn’t end, but the last part before the lights go out is a jubilant improvised dance set to Miami Sound Machine’s “Conga” under disco lights during which Valencia traverses the white line, the stage, the seats, and the aisles. She says/writes “THIS IS WHAT I LOOK LIKE / WHEN I DANCE FOR MYSELF IN FRONT OF YOU” and you are suddenly there with her rather than watching.16 Multicolored spotlights cast her sharp, moving silhouette on the walls as she alternates among salsa steps and ecstatic movement, using all the neglected corners of the space. Dancing for myself in front of you seems an apt and comforting rendering of pandemic sociality, where dancing together happens without proximity, across spans of space and time (zones), together but not, alone but not, conjuring co-presence.

The final dance for us feels like a thank-you gift from the narrator for travelling with her among the star points of many histories that make up her history, that now make up our histories. In her “Medley of Observations” at the start of Album Valencia tells us, “Sometimes the second time you see someone, you just know you’re going to keep trying to see them again.” What we seek in the next encounter is more of the vitality that happened in the first, a vitality we’ve decided is the best thing that could possibly happen to us right then in the collage of who we are, without which we feel our history will be impoverished somehow. Autobiography is a traversal of the self’s limits. “Bodies need space and part of the giving is in the take.”17 The queer part is knowing that this is what’s happening.

Image captions/credits:

- “VAMPIRE TIME.” Mariana Valencia, Album (Brooklyn, NY: Wendy’s Subway, 2018): 37.

- “THE LESBIAN DILEMMA.” Mariana Valencia, Album (Brooklyn, NY: Wendy’s Subway, 2018): 14-15.

- The line. Mariana Valencia, Album. Photo by Ian Douglas.

-

Mariana Valencia, Album (Brooklyn, NY: Wendy’s Subway, 2018): 22. Throughout I will be using this published script/collage to reference lines that Valencia delivers in the performance. ↩

-

Ibid., 11. ↩

-

Emplotment is narratologist Paul Ricoeur’s preferred way of explaining the plasticity and idiosyncrasy with which an author assembles the beats of a plot, a manipulation that “reveals itself to the listener or the reader in the story’s capacity to be followed.” Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, Volume 1, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago, IL: U Chicago Press, 1990): 66. See also Joe Baker, Configuration and Narrative Emplotment, https://figuration.al/configuration-and-narrative-emplotment-649c1500f317. ↩

-

Valencia, 8. ↩

-

Dagmawi Woubshet writes about divergent “calendars of loss” that emerge when Black communities’ losses to AIDS are considered not in relation to the white men who have been the primary cultural figures of the early years of the pandemic, but within an ongoing history of Black catastrophe. The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015): 8. ↩

-

Valencia, 34. ↩

-

As Valencia tells us, Assotto Saint “was a writer, activist, performer, punk musician. He was alive. He lived from 1957-1994. Assotto Saint was Haitian-born and lived most of his life as an artist in New York where he died of AIDS.” Valencia, 38. ↩

-

Ibid., 38-39. ↩

-

Ibid., 39. ↩

-

Ibid., 18. ↩

-

Thank you to the team at PICA for access to the Time-Based Art Festival that made this piece possible. ↩

-

Ricardo Montez, Keith Haring’s Line: Race and the Performance of Desire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020): 110. ↩

-

I’m moved here by Christina León’s theory of “opacity as a visual concept that disrupts logics of visibility and concentrates on the textures of relation rather than producing demographic knowledge.” Curious Entanglements: Opacity and Ethical Relation in Latina/o Aesthetics, https://manifold.umn.edu/read/64316c7b-6f7a-445f-8922-47a5f61ee512/section/0c944566-e483-4980-8e04-cdbc335f0326#ch10 ↩

-

Valencia, 15. ↩

-

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, A Dialogue on Love (London, UK: Beacon Press, 2000): 168. Thank you to William Orchard for recently reminding me of this passage. ↩

-

Valencia, 58. ↩

-

Ibid., 17 ↩

Roy Pérez is a writer and professor who teaches at the University of California San Diego. His writing appears in the LA Review of Books, Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (MIT Press, 2017), Narrative, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States (OSUP, 2017), Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory (25:3, Nov. 2015), Bully Bloggers, FENCE Magazine, and other places. Roy is co-editor, with Kadji Amin and Amber Musser, of “Queer Form,” a special issue of ASAP/Journal (2:2, May 2017). He is writing book on race, sex, and closeness in queer Latinx art and performance titled Proximities.

Mariana Valencia is a choreographer and performer, she makes work that compounds dance and text, and her subjects are both marginal and popular. By juxtaposing humor and gravity, speech and movement, song and silence, she creates a world that enables the audience to learn about themselves as they learn about her. Valencia is an LMCC Extended Life grantee, a Whitney Biennial artist, a Bessie Award recipient for Outstanding Breakout Choreographer, a Foundation for Contemporary Arts Award to Artists grant recipient, a Jerome Travel and Study Grant fellow, and a Movement Research GPS/Global Practice Sharing artist. Her work has been commissioned by Baryshnikov Arts Center, The Chocolate Factory Theater, Danspace Project, The Whitney Museum, The Shed and Performance Space New York. Valencia has toured nationally and internationally in Korea, England, Norway, Macedonia and Serbia; her residencies include AUNTS, Chez Bushwick, New York Live Arts, ISSUE Project Room, Brooklyn Arts Exchange, Gibney Dance Center, Movement Research, and the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (OR). Valencia is a founding member of the No Total reading group and she has been the co-editor of Movement Research’s Critical Correspondence. She’s worked with Lydia Okrent, Jules Gimbrone, Elizabeth Orr, AK Burns, Guadalupe Rosales, Juliana May, Em Rooney, robbinschilds, Kim Brandt, Morgan Bassichis, Jazmin Romero, Fia Backstrom and MPA. Valencia has published two books of performance texts, "Album" (Wendy's Subway) and "Mariana Valencia's Bouquet" (3 Hole Press).